Lab-to-Lab: US-Russian Lab-to-Lab Collaboration Story [Archived]

Early Lab-to-Lab | Export Control | Nielsen Jr. | Symposia | WSSX

Physics | Reminiscences of Russia | Caroline (Cas) Mason

- Setting the Stage

- Forming Collaboration

- Frequent Experimental Campaigns Part 1

- Frequent Experimental Campaigns Part 2

- Broadening and Declining Collaboration

- Restoring Collaboration

- Epilogue 2006-2016

- Concluding Remarks

February 1995

In February, 1995, the LANL team (B. Anderson, Ekdahl, J. Kammerdiener, Reinovsky, Rodriguez, Veeser, Younger, W. Zerwekh, and myself) travelled to Russia for the fourth experiment at VNIIEF in seventeen months, this time for a period of more than three weeks to conduct an experiment in which a VNIIEF DEMG was used to power a novel VNIIEF-designed x-ray production concept.

On three different occasions on travels throughout Moscow, Pat Rodriguez, who has a dark complexion, was stopped by Russian soldiers (not policemen) and his passport was inspected. Evidently the soldiers were part of increased security throughout Moscow because of the Chechnya situation, and Rodriguez was suspected of being a Chechnyan terrorist. Fortunately, the passport appeared legitimate and Rodriguez was not detained.

Upon arrival and check-in at Moscow’s Bykovo airport prior to the flight to Sarov, the team became rather concerned as they were taken to and boarded an airplane that was covered with more than six to eight inches of ice and snow. However, after the team sat in the cold, covered plane for 15-30 minutes, a truck with a jet engine mounted to it approached the plane, aimed the jet engine exhaust directly at the plane, and proceeded to de-ice the plane. The plane shook roughly as the jet engine exhaust passed over the wings and fuselage. A surprising, but effective, safety measure!!!

Los Alamos County had seen an unprecedented opportunity to participate in the growing peaceful relations between the two nations by providing assistance and friendship to Sarov as it underwent the transition from a “closed” city to an “open” one, the same transition that Los Alamos underwent some forty years previously. Our frequent visits to Sarov gave us an opportunity to act as “messengers” between the cities of Los Alamos and Sarov. A meeting with the Sarov city administration showed us just how enthusiastic Sarov was about the growing relationship. We were told that Sarov had joined the Russian Sister Cities organization, had become a member of the International Association of Sister Cities, and had formed a local sister cites organization. Furthermore, we were told that exchange visits, including visits to Sarov, were now a real possibility and we were given a formal invitation for a Los Alamos delegation to travel to Sarov for the upcoming May 9 50th anniversary celebration of the end of “the Great Patriotic War.”

As a result of this invitation, a delegation of seven Los Alamos citizens became the first US civic delegation to visit Sarov when they were in the city from May 3 until May 10, 1995. Included in the delegation were the chairman of the Los Alamos County Council, a middle school teacher, a librarian, a representative of the Los Alamos Chamber of Commerce, two housewives with extensive involvement in community activities, and an assistant editor from the Los Alamos Monitor newspaper. The Monitor representative was apparently the first US media representative permitted into the city by the Russian government. An Arzamas-16 Courier newspaper article describing this unprecedented visit ended with the statement “if all Americans are like these people, then you and I will not perish on this fragile planet.”

As a gift to the Los Alamos County Council, the Sarov city administration presented us with a brass bell that weighed about 25 lb. and stood about 10 inches high and contained engravings depicting Saint Seraphim (the most famous of the early residents of the ancient Sarov monastery, which is now surrounded by the city) and the Mother of Kazan (the patroness of the Russian army). After the meeting, Bob Reinovsky dutifully carried the cumbersome bell about 0.75 miles back to our hotel and we struggled to pack the bell in our luggage.

And as previously indicated, the frequent visits provided us with continued opportunities to interact with the Sarov medical community. The Arzamas-16 Children’s Medical Fund had recently leveraged $10,000 in donations from the Los Alamos chapter of the American Chemical Society into a shipment of medical supplies having a US wholesale value of approximately $500,000. A special Sarov medical team had been formed to distribute the supplies. Some supplies had been taken to the “delivery house” (maternity ward) and the “reanimation department” (intensive care ward). The medical shipment had been the subject of a special broadcast program and newspaper article. We were told “all hospital workers know the source“ and “many people were happy to volunteer to help with translations of the documents.” Evidently, the shipment took only a week to cross the ocean but nearly two months to process the documents. Ironically, Sudafed (a common US allergy medicine) included in the shipment had not yet been approved for use in Russia.

The bell given as a gift from the Sarov city administration to the Los Alamos County Council (February 1995).

We truly felt welcomed by the community on this trip. Tours inside and outside the city, school visits, and several concerts were arranged by our hosts. Opportunities were provided for cross-country skiing and Brodie Anderson even made a few runs on Sarov’s “downhole” (as opposed to downhill) skiing area in an abandoned quarry. Security restrictions had been relaxed enough that Bob Reinovsky and I were able to visit the home of a teacher from school #15, where we were treated to delicious Russian cuisine. The four school #15 students who had traveled to New Mexico with us in April, 1994 joined the group for reminiscences about the trip to Los Alamos. Exceptionally musically talented, the four students who had won the hearts of Los Alamos during their visit entertained the group with a series of Russian and English songs.

A poster commemorating the growing Sister Cities relationship and the April 1994 visit by Sarov students to Los Alamos hangs in Sarov school #2 (February 1995).

We continued to witness the remarkable resurgence of the Russian Orthodox Church. At Sanarksarsky Monastery we met with one of the 70 monks who resided at the monastery reopened only several years earlier and who told us how the monks from this monastery were taken to Sarov in 1923 and executed along with monks from the Sarovsky Monastery.

One of the most memorable scenes of the trip occurred on a visit to the shrine of St. Seraphim outside Sarov, but still within the security fences. In the quiet and beauty of the Russian winter, small prayer candles were found burning in the deep snow at the base of a small cross and through the forest we heard the beautiful sound of several women singing chants a cappela in front of another cross, perhaps the most spiritually moving event of all my time in Russia.

Candles glisten in the snow as Sarov women sing chants a cappella at a cross nearby (St. Seraphim shrine, February 1995).

September 1995

Another joint experiment to obtain data on the MAGO plasma formation scheme was conducted at VNIIEF. The 11 technical members of the LANL team (Anderson, Ekdahl, Goforth, G. Idzorek, H. Oona, T. Petersen, Reinovsky, P. Sheehey, Shlachter, Younger, and myself) were accompanied for the first time by a LANL interpreter (S. Shachowskoj) and spent essentially three weeks in Russia. This experiment involved the most LANL participation to date, with approximately 4,000 lbs. of LANL equipment being used to record many dozens of data channels.

For the first time, VNIIEF scientists were permitted to escort us for many of the technical activities without the need for a member of the security forces. Evidently, VNIIEF scientists who had visited LANL had reported to their security officials that LANL scientists, and not LANL security personnel, had acted as their escorts. However, they apparently did not report that LANL regulations set a limit of three foreign scientists per escort, so the VNIIEF scientists escorted larger groups. LANL’s influence was also noticed in the “list of prohibited items” that we were all required to sign, a list remarkably like that used at LANL.

Once again, winter had arrived before the Sarov central heating plant had been put into operation after a summer interlude, and temperatures in our hotel rooms dropped to as low as 56 degrees Fahrenheit.

As an indication of the growing trust of the LANL participants, security restrictions on the team’s movements about town for technical and social activities were far more permissive than on previous visits. In-home visits, English Club meetings, and even tennis had become almost commonplace. School visits had mixed emotions for us as students with whom we had become acquainted on our first visits had now graduated. Several members of the team were taken through the catacombs under the city that dated back to 1697.

The LANL team meets with the Sarov English Club (September 1995).

A weekend excursion took us to the city of Nizhni Novgorod, some 120 miles north of Sarov. Upon arrival in Nizhni Novgorod, I realized that I had left my passport in Sarov. Under the Soviet system, this would have been a major security breach. When the hotel would not issue a room to me, our VNIIEF host took me alone on the team’s bus to several government offices throughout the city. Although I could not understand the Russian being spoken, it appeared that no office knew how to handle the situation and referred the host to yet another office. Finally, the contingent returned to the original hotel with no apparent resolution at hand. Nevertheless, I was then issued a room.

One of the more inspiring events of our trip to Nizhni Novgorod was a visit to the apartment where Andre Sakharov had spent his exile, once again reminding us how remarkable it was for the LANL and VNIIEF teams to be working together. As many times before, we wondered how Sakharov would have viewed our collaboration and, in a way, we felt cheated because he had not lived long enough to witness the remarkable relationship developing between his institution and Los Alamos. We were to learn some years later that the apartment, which had been turned into a museum, included a display about the joint experimental effort.

The author at the apartment where A. D. Sakharov was held in exile (Nizhni Novgorod, September 1995).

Two of the team members had roots in Russia, making the trip all the more meaningful for them. LANL interpreter Sergei Shachowskoj’s father had fought in the White Army, and his stepfather had spent time in a Soviet jail. Sergei’s family had come to the U.S. when Sergei was a young man. Sergei had returned to Russia more than sixty times prior to this trip, but this trip was special because a Shachhowskoj family estate was located along the road between Sarov and Diveevo.

Tom Petersen, making his first trip to Russia, had “Volga German” grandparents who had immigrated to the U.S. in 1910. Prior to departure from the U.S., I had contacted Sarov and VNIIEF officials to see if a trip to Saratov, Petersen’s grandparents’ home, could be arranged. From the beginning, Petersen had offered to pay all expenses as well as a fair daily wage, and there was some hint that some unsavory residents had vied for the opportunity to obtain American dollars. Nevertheless, the VNIIEF and Sarov administrations enthusiastically worked to make the trip possible, including the necessary arrangements with VNIIEF security. Victor Pavlenko, a retired school principle who had relatives in Saratov, and his daughter, Olga, an English teacher who also worked as a VNIIEF interpreter and who would several years later marry LANL scientist Ron Augustson, were selected to accompany Petersen. While the remainder of the team was spending a weekend in Nizhni Novgorod, Petersen and Anderson had what Petersen would describe as “the trip of a lifetime” to the land of his grandparents.

By this time, the LANL/VNIIEF collaboration was generally well known throughout Sarov. During this visit, four separate articles covering the joint experiment and interviewing LANL team members appeared in the Sarov Courier newspaper.

August 1996

Again a large LANL contingent (Anderson, D. Clark, Ekdahl, R. Faehl, Goforth, Petersen, Reinovsky, L. Tabaka, and me) travelled to Sarov for nearly three weeks to conduct a joint experiment. The experiment provided our first opportunity to work with VNIIEF’s pulsed power “flagship,” the 1-m-diameter Disk Explosive Magnetic Generator (DEMG). The experiment would be the largest electrical current, the highest electrical energy, and highest magnetically driven liner kinetic energy experiment ever involving U.S. scientists. Because approximately 770 lbs. of high explosive were detonated in the experiment, the bunker shook noticeably more than on previous experiments.

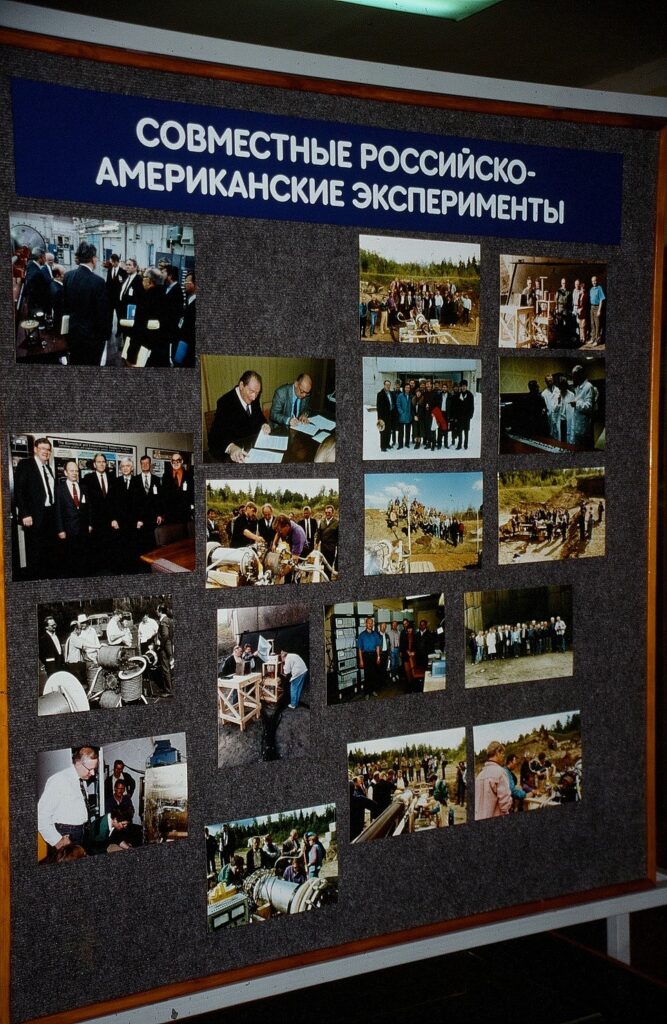

A poster at the VNIIEF museum commemorates the joint LANL/VNIIEF experiments (August 1996).

When we emerged from the bunker, several small fires were noticed in the grass and brush adjacent to the firing point, and a column of smoke was rising from the forest perhaps 200-300 m away from the explosion point. To our surprise, a loud heavy, powerful tracked vehicle carrying water and pumps came roaring out of the forest essentially unimpeded by the trees and undergrowth in its path as it trampled trees while it squelched the blazes initiated by the debris of the experiment.

Several team members carried with them numerous copies of a special issue of Los Alamos Science entitled “US/Russian Collaboration to Reduce the Nuclear Danger.” The books were passed to VNIIEF administrators and scientists and to social acquaintances. The recipients seemed to take pride in their contributions to the collaboration.

Once again, our VNIIEF hosts planned an extensive social and cultural schedule for the team. These events reminded us that, in addition to conducting state-of-the-art research, we were filling a very important role as ambassadors for our nation and our laboratory. The warmth with which we were received in Sarov made us realize that we had not only won the trust and respect of the scientists but also the entire community.

The people of Sarov were making an impression on us, as well. The joy of meeting new friends at the English Club prompted Anderson in his spare time to write some beautiful poems that expressed many of the feelings that both the Russians and the Americans had. Impromptu concerts on the “garmmuk,” an accordion-like instrument, by Sergei, our bus driver, brightened our days but also saddened them as Sergey told us about his father’s memories of World War II.

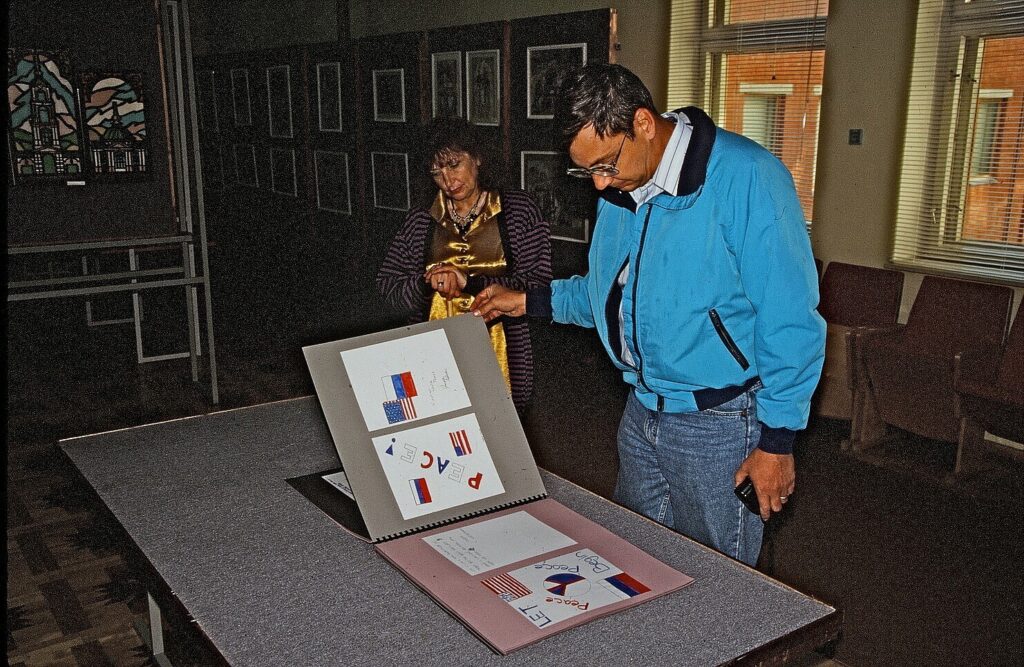

At the VNIIEF museum, Tom Petersen examines the Friendship Book that had been sent in January 1994 to Sarov students by Los Alamos students (August 1996)

The Sarov city administration asked us to carry a shipment of children’s artwork to Los Alamos for an upcoming art exhibition, “Art from Sarov, our Sister City.” Because we were given papers indicating that all work had been approved for export by all cognizant Russian authorities, and all packages had the appropriate stamps, the material passed through Russian customs with no problem. Lufthansa airlines in Moscow checked the delegation in as a group, so there was no extra luggage charge for the eight tightly wrapped packages.

However, in Frankfurt, when asked, I informed security personnel that I had not personally seen the packages packed and did not know with certainty what was contained in them. Therefore, I was escorted down to the tarmac under the huge Delta plane where all packages were opened in the presence of an inspector. To my surprise, the shipment contained not only children’s art of limited value but also a number of clearly professional pieces of unknown, but apparently high, value, leaving me to ponder for the entire flight what would happen at U.S. customs. Fortunately, U.S. customs passed the shipment without imposing the substantial import duty that was probably warranted.

Prior to the start of the experimental campaign, a large LANL contingent including Ekdahl, Goforth, Reinovsky and myself had participated in the Seventh International Conference on Megagauss Magnetic Field Generation and Related Topics. As previously mentioned, the Megagauss conferences had set the stage for the LANL/VNIIEF collaboration. As an indication of the increasing openness in Russia, the first days of the conference were held entirely within the security fences of VNIIEF. Chernyshev, the Technical Program Committee chairman, said in his opening remarks that “we could only dream 3-4 years ago [at the last conference] that we would gather on Sarov soil.” Chernyshev described the impact of Max Fowler’s 1965 paper on megagauss magnetic fields as “like a bomb exploded” and emphasized that “it is not too strong to say that these conferences have contributed to world peace.”

The author (left) swims in the Satis river with Los Alamos colleague Dave Scudder (August 1996).

As part of the conference opening ceremonies, I was asked to accompany the family of Alexander Pavlovskii to place flowers on Pavlovskii’s grave. The warm weather provided our first and only opportunity to swim in the Satis river; unfortunately, we weren’t able to swim with V. N. Mokhov, whose home sat along the river and who always spoke about his enjoyment of being able to swim in the river.

November 1996

Anderson, Petersen and I returned to Sarov only one-and-one-half month after our previous departure. Bartsch and Ladish completed the team that was in Sarov to bring into operation a set of LANL-owned diagnostic equipment being provided for VNIIEF use on a project sponsored by the International Science and technology Center (ISTC) and to test the equipment on the first of several ISTC-sponsored MAGO magnetized plasma experiments.

It was certainly beginning to seem like the presence of someone from Los Alamos created a certain excitement in Sarov. Nearly every day Sarov residents stopped by our hotel or stopped us on the streets to pass letters to us or to send greetings to their friends in Los Alamos. Evidence of Los Alamos was seen throughout the city, including the hotel lobby (a copy of Los Alamos Science), the museum (the 200-page Friendship Book from Los Alamos students), and the city administration building (a life-size photo of a joint experiment). A number of Russian-language publications included pictures of Los Alamos scientists and residents. One quoted the Sarov mayor as saying

From my point of view, the key to this program is our young generation. For the sake of its future we are establishing these contacts, so that our young people learn to understand another nation. Last year, our children visited Los Alamos; this summer American children will come over. This is more important than economic or technical cooperation. This is our younger generation’s future, the future of Russia.

The now-common visit to the English club had a special surprise as a 13-year-old daughter of one of the members recited one of Brodie Anderson’s poems in perfect English. A meeting with city officials reviewed the past and upcoming Sister Cities exchanges that now included physicians visits as well as students, teachers, and city administrators. Ladish remarked afterwards that in Sarov and Russia we were seeing a democracy being born, and that Los Alamos had an unprecedented opportunity to be part of this process.

Because LANL travelers to Sarov often found it necessary to carry large amounts of cash to Russia, I had begun to investigate the possibility of “wire transfers” of money between US banks and the bank in Sarov. Just prior to this trip, as an experiment, I transferred by wire $100 from my Los Alamos bank account to the Sarov bank (the Los Alamos bank charged a $35 fee for this service!!!). My US passport number was included in the transfer document for identification purposes.

Sure enough, my visit had been expected by the Sarov bank and a number of documents had been prepared for my signature. I was given a Sarov bank account number and passbook specifying, in dollars, the account balance and a statement that, at present, the bank was paying 3% annual interest. Evidently, the account was one of a growing number of “currency” accounts, as opposed to Ruble accounts where the balance is specified in Rubles. I withdrew $50 (a choice of Rubles or actual US bills was given). Because the money had been wire-deposited, rather than direct-deposited, a 2% fee ($1) was charged for the withdrawal, leaving a balance of $49 that may still remain today even though the account has been dormant for more than 20 years. A bank manager pointed out that in the near future (e.g., six months) wire-transfers would not be necessary because he expected to install a capability to accept Visa cards for cash withdrawals.

Next >> A broadening and yet declining collaboration 1997-1999 >>