April 14, 2022

Tricia A. White

Putin’s War with Ukraine: Voices of CNS Experts on the Russian Invasion

Tucked upstairs at the Center for Nonproliferation Studies is a common room where students bustle between graduate classes and open-source work as graduate research assistants. Among the stacks of books and old aerial imagery, my teammates roll along the carpet in desk chairs asking each other for a second set of eyes on whatever we’re working on: annotating a satellite image, mapping out a facility, or modeling a missile. If the sign of a good team is that every person brings a different perspective to the conversation, we’re great. If we all crowd around a video and notice something different, we are doing our jobs as analysts.

February 23rd was pretty much a normal day. I was working with some colleagues to estimate the size of an Iranian missile. Another GRA was looking at new radar images taken by satellites of Russian military units. Another was watching a performance of a North Korean K-Pop group, hoping to spot hard-to-find images of missiles in the giant slideshow they were singing in front of. (I love terrible North Korean K-pop. I listen to it when I cook.)

Like everyone else, we habitually check social media, like Twitter. (I cannot imagine what it was like to work in this field without reading every single opinion every person has ever had. I imagine people before Twitter were extremely productive and it was much easier to go home and not continue working, but I digress. Ed note: We were not.) I was spending a lot of time looking at videos of Russian military equipment on TikTok.

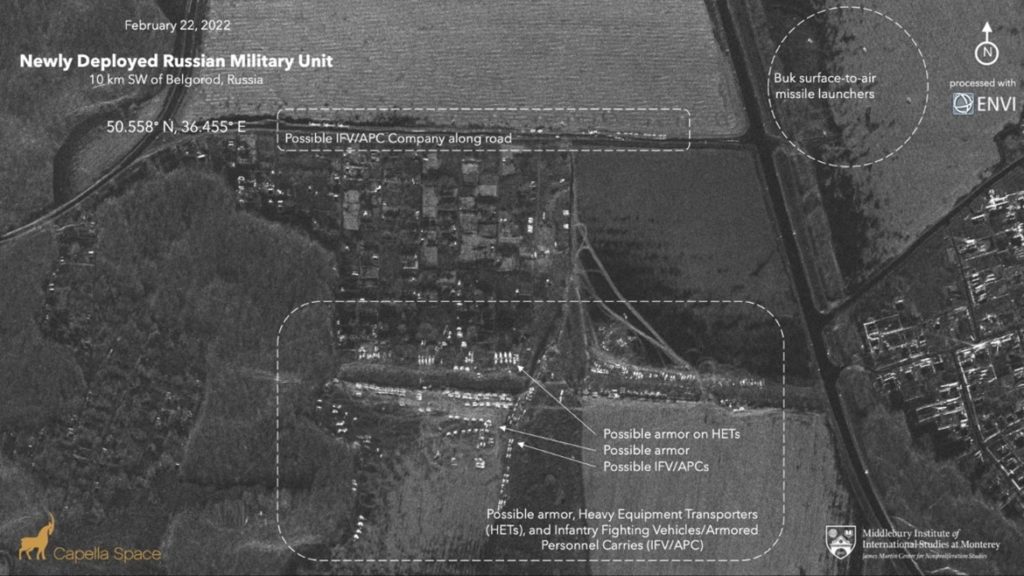

Watching the Russian buildup around Ukraine, an invasion seemed inevitable – it was only a matter of when. The day before, one of our GRAs, Steven De La Fuente, had spotted a Russian military unit in a radar image taken by Capella Space. This unit looked different from other Russian military units. In open-source work we look for deviations from what appears normal. The vehicles were organized just off the highway in a formation ready to move out – they were not setting up camp. Thanks to a tip, I tracked down a TikTok video taken of the same unit on the highway. There were many armored vehicles, getting ready to invade Ukraine.

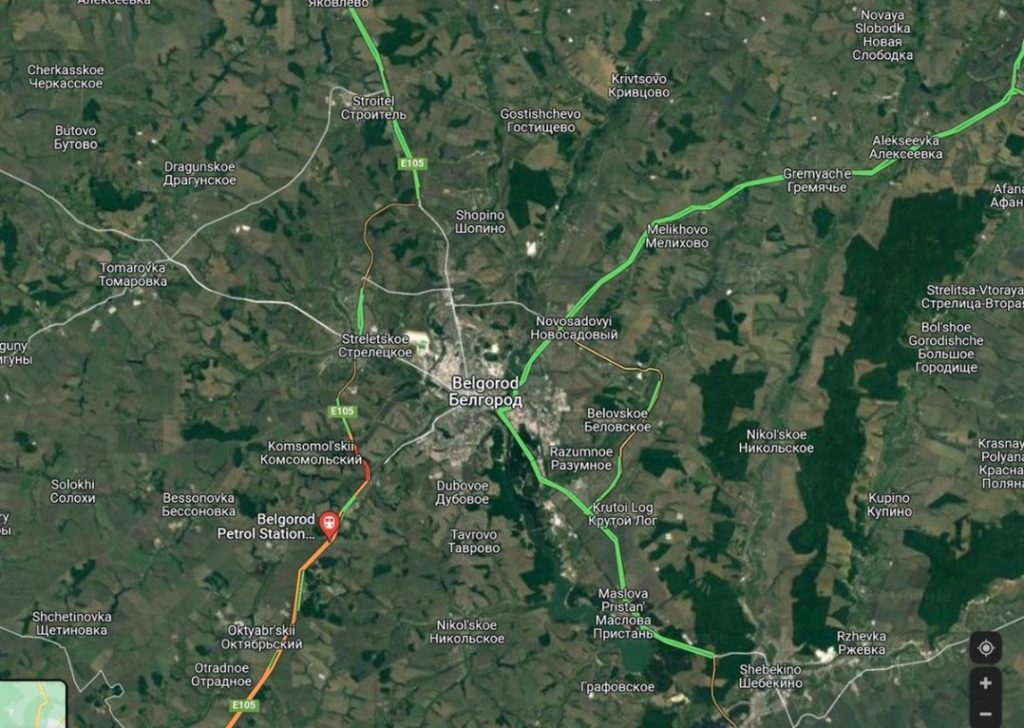

That afternoon, I went back to measuring missiles. John Ford, another student, decided to look at Google Maps. He was curious whether Russian military activities might disrupt normal traffic patterns. A little after 5 pm California-time, John called out from his desk that there was a traffic jam at the exact location of that Russian armored unit. That was about 3:00 am local time. There aren’t often traffic jams in the wee hours of the morning. Even so, we were nervous to make the call. Did we just see the war start on Google Maps? Dr. Lewis was not nervous. He was on his phone, telling people the invasion was starting. And then he tweeted it.

From that moment forward, all other work in the office screeched to a halt. Michael Duitsman and Ben Mueller started looking for livestreams of Ukrainian cities, putting them up on the computer monitors. We watched the bright red “traffic jam” on Google Maps slowly inch towards the border.

We ordered pizza and settled in. About an hour later, President Vladimir Putin announced a “special military operation” for the “denazification” of Ukraine. Watching the livestreams on our computer monitors, we could see explosions in Ukrainian cities. The war really had begun

This night was the first time my work was in response to a real time crisis. I was running on the adrenaline that kicks in during a tragedy – the human effort to help as much as possible, even knowing that I was thousands of miles away. Some of my colleagues are old enough to remember the September 11th attacks. I am not. For them, that’s what the moment felt like. To me, it was a moment with no precedent.

We worked late, plumbing the depths of the internet for images and videos from Ukrainian and Russian civilians to give us an indication of where Russian troops were heading. Verifying social media information from Telegram. Downloading more satellite imagery to anticipate the course of the war. Another student, Lisa Levina, helped us translate videos and politely corrected our pronunciation. Dr. Lewis encouraged us to share what we were finding. As student analysts watching a deadly conflict, most of us were wary about speaking publicly. What if we made a mistake? Looking back on that night, I realize it was a turning point in my career. My work is real work. I had to learn to trust my skills and be willing to share my research.

In the weeks since the war started, our team has continued to provide evidence-based information to the public. As Russian forces retaliated against civilians for sharing information on social media, shut down CCTV cameras, and turned off power in Ukrainian cities, we have had to shift our strategies to follow the conflict. Of course, nothing posted on Twitter will halt the Russian invasion. We are not decision makers; we are informers, teachers, and factfinders. I only hope that our work reaches those who choose to take action and strive for peace.

Tricia A. White is an M.A. Candidate Nonproliferation and Terrorism Studies at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey.