April 13, 2022

Sanaa Alvira

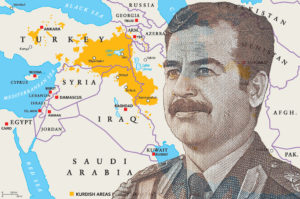

Saddam Hussein and Kurdish areas in the Middle East (Src: Shutterstock)

Last week, US President Joe Biden called his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin a “war criminal” over the killing of civilians in the Ukrainian town of Bucha. The Kremlin claims that the mass graves and corpses in Bucha were staged by Ukraine to tarnish Russia’s image, and it continues to deny all allegations of war crimes in the course of what it calls its “special military operation.” This pattern of denial is not unique to Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Whether to preserve domestic or international support or to avoid criminal liability, leaders of authoritarian regimes in particular tend to distance themselves from atrocities that their forces have committed. These habits of opacity make it difficult for investigators to definitively assign responsibility for a government’s misdeeds.

In new research published in the Nonproliferation Review, David D. Palkki and Lawrence Rubin illuminate the difficulties of attribution and accountability for war crimes by probing whether Saddam Hussein, Iraq’s leader, directly ordered a chemical-weapons attack on civilians in the Kurdish town of Halabja in 1988. The authors note the absence of any record of an explicit order to gas Halabja. But after probing the “command environment” created by the leader, they also reject any conclusion that the act took place purely at the initiative of Saddam’s subordinates.

Contradictory claims

David Palkki

Saddam Hussein gave conflicting accounts after his capture in December 2003. FBI interrogator George Piro claimed that Saddam had said that gassing Halabja was his decision, but according to John Nixon of the CIA, Saddam flatly denied having issued such an order. Saddam’s key subordinates also told conflicting stories. While former military officials claimed that the order came from the very top, Saddam’s trusted advisor Tariq Aziz claimed that the leader did not order the attack and even responded by withdrawing his permission from top military leaders to use chemical weapons.

These contradictions cast doubts on the significance of claims made in captivity. All of the figures involved, including Saddam himself, understood the need to deflect blame for atrocities to protect themselves from prosecution. Yet it also may be possible that Iraq’s top military officials had the latitude to decide upon carrying out chemical attacks against Kurdish insurgents.

Contemporary records

Lawrence Rubin

Seeking further insights, the authors explore the regime’s own records. In a captured transcript, Saddam seemed to have reservations about the timing of the operation in the Kurdish areas of northern Iraq, being more preoccupied with an Iranian offensive in the south. An internal memorandum, consistent with Aziz’s testimony, hints that Saddam might have chosen to distance himself from the attack after learning the extent of the massacre. But other records, particularly in the year before the attack on Halabja, portray Saddam as intimately involved in all decisions to employ chemical weapons.

Following the leader’s will

A more holistic understanding of the records finds that Saddam did not express remorse about the slaughter in Halabja. None of the military officials involved faced demotion or disciplinary action; afterwards, Saddam even decorated the perpetrators of the broader “Anfal” campaign against Iraq’s Kurds. The ambiguity of evidence for a specific order from the top may even have been purposeful, reflecting a pattern common to many authoritarian regimes, in which subordinates are expected to anticipate and carry out the leader’s will without waiting for explicit guidance.

With or without any record of personal orders, the paramount leader is ultimately responsible for a command environment that promotes atrocities. Palkki and Rubin note that if Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad is ever held to account for similar crimes in recent years, the Iraqi experience “should temper expectations” about what sort of evidence will be available, but the absence of a full paper trail cannot be considered exculpatory. The same points now may apply to Russia’s Putin as well.

Read this NPR article

About our journal

The Nonproliferation Review is a refereed journal concerned with the causes, consequences, and control of the spread of nuclear, radiological, chemical, and biological weapons. The Review features theoretical analyses, historical studies, viewpoints, and book reviews on such issues as state-run weapons programs, treaties and export controls, safeguards, verification and compliance, disarmament, terrorism, and the economic and environmental effects of weapons proliferation.

The Nonproliferation Review is produced at the Washington, DC offices of the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey. The journal is published by Taylor & Francis.