Michael Jasinski

Cristina Chuen

Charles Ferguson

May 27, 2002

The uncertainty over the nature of activities at the Novaya Zemlya nuclear test site in northern Russia has frequently been a factor in US government decisions on stockpile stewardship and participation in international treaties. The lack of transparency at the two countries’ test sites has contributed to mutual suspicions and calls by some parties in both countries for the resumption of testing.

Most recently, Bush administration officials have held a number of closed briefings with members of the US House of Representatives and Senate on alleged Russian preparations to resume underground nuclear tests on the Novaya Zemlya nuclear test site reported in the New York Times. The Joint Atomic Energy Intelligence Committee concluded that such preparations are underway based on work which reportedly matches the pattern of Russian preparations for conducting a nuclear test. (1) While the White House did not comment on the New York Times report, the spokesman for the National Security Council stated that there was concern that the United States might not be able to detect some nuclear tests, and that it expected Russia to abide by the testing moratorium, which has been in force since 1992. (2)

Russian Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov has denied these reports, however, and requested that the Bush administration provide explanations for such claims, which he deemed incompatible with a new US-Russian strategic relationship based on mutual trust and respect. (3) In an appearance with Ivanov on a Russian television program, US Secretary of State Colin Powell stated that the United States did not intend to resume nuclear tests and that its own testing moratorium remained in force. (4) In a separate statement the Russian Foreign Ministry again denied the claims of preparations for resuming nuclear tests, adding that the test site was already in a state of readiness, and was being used for activities not covered by nuclear testing treaties. The Foreign Ministry also accused the US government of attempting to distract world opinion away from the US failure to ratify the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), which Russia ratified on June 30, 2000, and US plans to develop new types of nuclear weapons. The ministry also noted that the report has led the House of Representatives to adopt legislation lifting the restrictions on conducting research on new types of nuclear warheads. (5) Russia’s Defense Ministry, whose 12th Main Directorate has jurisdiction over the test site, also denied that preparations to conduct tests were underway, and added that the only activity planned for the Novaya Zemlya test site was another series of subcritical experiments (tests that do not result in a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction). These tests on Novaya Zemlya are usually held late in the fall due to the heavy snow cover prevailing during the rest of the year. Such experiments have been conducted since 1998. (6) The Russian government has already acknowledged on other occasions that it has conducted subcritical nuclear experiments. Five such tests were conducted in 2000 alone. (7) According to the Ministry of Atomic Energy only about 100 grams of plutonium were used in each of the tests, which were conducted to verify the safety and reliability of Russian nuclear warheads. Similar experiments have been performed by the US Department of Energy at the Nevada Test Site, and are not banned by any existing nuclear testing treaty. (8)

Russian Nuclear Testing and Stockpile Stewardship

Although Ivanov’s statement is likely to reflect Russia’s policy for the foreseeable future, in Russia as well as in the United States the nuclear testing moratorium has been a controversial subject, with a number of highly placed officials calling for the resumption of nuclear testing. Ever since the beginning of the moratorium the senior leadership of the 12th Main Directorate of the Ministry of Defense, which is entrusted with maintaining the security and safety of Russia’s nuclear warheads, has periodically issued statements that testing was needed to ensure warhead safety. (9) In a 1995 interview, then-chief of the 12th Main Directorate General Yevgeniy Maslin worried that even though it was possible to preserve the safety of the nuclear weapons through computer modeling and subcritical tests, these methods were less reliable than actual nuclear tests. Maslin’s concerns are also shared by a number of other Russian specialists involved in preserving the safety of Russia’s nuclear weapons. (10) In March 2001, former Minister of Atomic Energy Yevgeniy Adamov discussed the possibility of Russia’s withdrawal from the CTBT. Adamov stated that while Russia is currently able to carry out its nuclear weapons program without conducting nuclear explosions, the CTBT provides for withdrawal from the treaty if the president deems its observance to be contrary to Russia’s national security interests. (11) At an April 11, 2002 press conference two former ministers of atomic energy, Viktor Mikhaylov (who occupied the post between 1992 and 1998) and Yevgeniy Adamov (1998-2001) both expressed the view that Russia will eventually face the choice of resuming tests or forgoing nuclear weapons altogether. Although mathematical models and computer simulations provide some assurances, in the long run tests would be required to confirm both the safety and reliability of nuclear warheads. In their view simulations and analysis of components of disassembled nuclear warheads only partially compensate for the absence of nuclear tests. Moreover, the former ministers also expressed concern that Russia was losing the expertise needed to conduct effective nuclear tests. (12)

Russian worries about the inability to conduct nuclear tests also stem from the fact that Russian nuclear warheads do not use “insensitive” conventional explosives, which are far less likely to detonate due to fire, shock, or gunfire damage than ordinary explosives. Although such explosives have been developed in Russia, the 1992 nuclear testing moratorium prevented Russia from fully testing them as a component of nuclear warheads. (13) The moratorium, combined with Russia’s economic crisis, has also had the effect of reducing Russia’s ability to conduct nuclear tests. Although attempts have been made to preserve the infrastructure, more than two-thirds of the nuclear test specialists at Novaya Zemlya have since left the site. (14)

Furthermore, although there are no indications the United States will ratify the CTBT or that the treaty will enter into force in the foreseeable future, any resumption of nuclear tests by Russia would entitle the United States to invoke verification rights under the Threshold Test Ban Treaty (TTBT), which was signed in Moscow in 1974 and entered into force in December 1990. TTBT limits the yield of nuclear tests to 150 kilotons and entitles Russia and the United States to conduct a variety of verification activities, including on-site inspection. (15) In the absence of the CTBT, which contains broader provisions for verification than the TTBT, there is also the potential for bilateral transparency measures that could reduce both sides’ uncertainty about possible testing activities. For example, on July 6, 2001, Yuri Ushakov, Russian Ambassador to the United States, toured the Nevada Test Site at the invitation of Senator Harry Reid (D-Nevada). Ambassador Ushakov is the highest ranking Russian official to visit the site. Although this visit was largely a goodwill trip, it could establish a precedent for the US Ambassador to Russia to visit Novaya Zemlya. (16)

United States Nuclear Testing and Stockpile Stewardship

The controversy over the alleged Russian plans to conduct nuclear tests on Novaya Zemlya has brought renewed attention to US stockpile stewardship activities and the question of whether the United States might resume nuclear tests. (17) In addition to the possibility of resuming nuclear tests in reaction to Russian developments, there are also internal US reasons increasing the pressure to resume tests.

During the test moratorium and in anticipation of the eventual entry-into-force of the CTBT, the United States geared up for the Science Based Stockpile Stewardship Program with the objective of ensuring the safety and reliability of the US nuclear stockpile without nuclear testing. (18) In October 1995, the Department of Energy (DOE) unveiled plans for six subcritical tests in 1996 and 1997 but stopped short of initiating these tests until after the 1996 CTBT negotiations concluded. On July 2, 1997, the first test, named Rebound, took place. More than a dozen have followed, and more are planned.

These subcritical tests have been carried out below ground, making it difficult for Russia to ascertain whether the United States blurs the line between permitted subcritical tests and prohibited hydronuclear tests. The latter tests are very low-yield nuclear tests in which as little as a few pounds worth of nuclear blast could occur. (19) In 1996, Frank von Hippel and Suzanne Jones recommended that the national laboratories conduct subcritical tests above ground in order to preclude crossing the threshold into low-yield tests. For safetys sake alone, designers of above ground tests would tend to err on the side of caution and ensure that there would be zero-yield. Further, von Hippel and Jones argued that above ground tests provide for more transparency. The United States and Russia can rely more readily on their national technical means, such as satellite surveillance, to provide confidence that no below ground activity is taking place. (20) In addition, the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty prohibits any above ground nuclear testing.

Is Renewed US Nuclear Testing on the Way?

In October 1999, the US Senate, after a perfunctory and partisan debate, voted against CTBT ratification. Many CTBT proponents charged, at the time, that the vote was primarily directed against President Clinton. Critics of the CTBT felt that it was unverifiable, thus allowing cheaters to go undetected. Supporters countered that the extensive global monitoring system and US national technical means of detection would be more than sufficient to catch cheating. Moreover, the CTBT has provisions for on-site challenge inspections. If the CTBT were in-force today, the United States could invoke this provision to investigate suspect activity at Novaya Zemlya.

Another motivating factor of CTBT opponents was to ensure that the United States would not be hemmed in by another arms control treaty. That is, the United States would have the flexibility to develop new nuclear weapons, depending on the US leaderships assessment of national security needs. A year after the defeat of the CTBT, the first shot across the bow toward possible new nuclear weapons development was fired when Senators John Warner (R-Virginia) and Wayne Allard (R-Colorado) introduced legislation calling for a Department of Defense (DOD) and DOE study on the defeat of hardened and deeply buried targets. (21) Although this legislation passed, it did not explicitly override the 1993 Furse-Spratt legislation prohibiting the national laboratories from research and development leading to a precision, low-yield nuclear weapon. (22)

The Bush administration has made clear its stance on the CTBT. It opposes CTBT ratification but still supports the testing moratorium. In 2001, the administration demonstrated its disdain for the CTBT. It boycotted the November 11-13 UN conference on the treaty. Just a week prior to this conference, the administration called for a vote on whether to place the CTBT on the UN General Assemblys agenda and then voted against the proposal. (23) In August, although the administration provided most of its assessed funding for the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), it decided to not fund treaty activities, such as on-site inspections. (24)

Early this year, the administration reiterated its position on the CTBT. For example, on January 9, Ari Fleischer, White House Press Secretary, said, And on testing, the President has said that we will continue to adhere to the no-testing policy, if that would change in the future, we would never rule out the possible need to test to make certain that the stockpile, particularly as it’s reduced, is reliable and safe. So he has not ruled out testing in the future, but there are no plans to do so. (25)

The administration is taking steps to accelerate Nevada Test Site preparedness for potential future testing. In the January briefing on the Nuclear Posture Review, the Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Policy, J. D. Crouch, stated that the United States will need to improve our readiness posture to test from its current two to three year period to something substantially better. (26) On March 21, 2002, John S. Foster, Jr., Chairman of the Panel to Assess the Reliability, Safety, and Security of the United States Nuclear Stockpile, told the House Armed Services Committee that the panel recommend (s) the administration and Congress support test readiness of three months to a year, depending on the type of test. (27) The administrations fiscal year 2003 budget request to Congress asks for $15 million to ramp up Nevada Test Site readiness. The total FY2003 budget request for the Stockpile Stewardship Program is $5.87 billion. This represents a 5.5 percent increase over the 2002 appropriation and an 18.5 percent increase over the 2001 appropriation. (28)

The drive for an effective missile defense system may lead to another reason for renewed nuclear testing. Critics of missile defense have raised concern that the currently under-development hit-to-kill method (in which collisions between interceptors and incoming ballistic missiles are used to destroy warheads) would be incapable of providing a successful defense. In April, a Pentagon advisory group raised the possibility of using nuclear-armed missile interceptors. This news soon stirred ire on Capitol Hill. Senators Ted Stevens (R-Alaska) and Dianne Feinstein (D-California) condemned this concept. (29) The political flak may have killed for now any hypothetical plans for nuclear-armed missile defense. If missile defense supporters eventually proceed down the path of nuclear-armed interceptors, they may call for nuclear testing to be assured that the new weapons would work. Perhaps they would dust off the old designs. The United States deployed in 1975 such a defense on the Safeguard system, which was dismantled in 1976. In the 1960s, Russia installed a nuclear-armed missile defense around Moscow. Uncertainty surrounds its effectiveness and operability. Even if nuclear-armed defense could effectively destroy missiles, adverse effects, such as electromagnetic pulses generated by outer space nuclear explosions that could harm civilian and military satellite communications, would strongly argue against pursuing these defenses.

There is no open source evidence indicating that Russia has done more than prepare for a resumption of nuclear testing on Novaya Zemlya, which it did after the United States indicated that preparations were underway at the Nevada test site as well. However, the political statements that are being made at present concerning these preparations increase the possibility that testing might be resumed. Therefore increased transparency measures are needed so that political decisions may be based on a clearer understanding of the situation and not in reaction to rumors.

Additional Activities on Novaya Zemlya

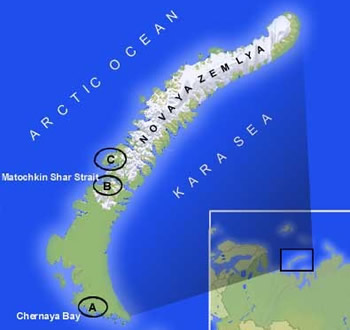

Novaya Zemlya Test Sites, Nonproliferation.org

Zone A (Chernaya Gulf region): low— and medium—yield atmospheric explosions, and underwater and surface nuclear tests (1955—1962); six underground tests (after 1963).

Zone B (Gulf of Matochkin Shar’s southern bank): nuclear tests conducted in deep underground shafts (1964—1990).

Zone C (Sukhoy Nos peninsula, north of Matochkin Shar strait): atmospheric tests (1957—1962).

Apart from nuclear tests, like its US counterpart in Nevada, the Novaya Zemlya test site has been evaluated as a site for a range of other activities, including nuclear waste storage. For more than a decade, Russia has been considering the storage of low—, medium—, and high—level radioactive waste, as well as spent fuel and nuclear reactors from nuclear submarines, on Novaya Zemlya. The first plans, for the storage of low— and medium—radioactive waste, including cesium and cobalt, were developed in 1991 by the All—Russian Scientific Research and Design Institute of Industrial Technology (VNIPI Promtekhnologii) and the All—Russian Scientific Research and Design Institute of Energy Technology (VNIPIET). A site on the south of the island, north of Bashmachnaya Bay, was selected, and construction of the storage site included in the special federal program “On the Treatment of Radioactive Waste and Spent Nuclear Materials, Their Recycling, and Their Disposal from 1996—2005.” (1) According to current plans, the facility will house radioactive waste from Northern Fleet nuclear—powered submarines as well as waste in temporary storage at the Mironova Gora site near Severodvinsk, Arkhangelsk Oblast. Public hearings regarding construction of the facility were carried out in 2001, and a positive environmental impact assessment was completed in March 2002. Construction will cost an estimated $73 million and take three to four years. (2) Russian environmental groups are protesting against the facility, saying that spending levels are too low to implement adequate safety measures, and that Novaya Zemlya lacks the infrastructure for constant radiation monitoring. (3)

A large solid radioactive waste and spent nuclear fuel storage facility may also be built on Novaya Zemlya. By May 2001, five 300—meter test shafts had already been drilled to test radioactive waste and spent nuclear fuel burying technologies. (4) The waste would be stored underground in 90—meter cement—lined shafts. Novaya Zemlya was chosen because of its permafrost conditions: groundwater can be found only at a depth of 600 meters. According to Nikolay Lobanov, scientific head of the project, the shafts can withstand a 150—megaton (MT) nuclear explosion and a 7.0 earthquake. (5) The project has been ordered by Atomredmetzoloto, and a design drafted by VNIPI Promtekhnologii; its main subcontractors are VNIPIET and Gidrospetsgeologiya. (6) The facilitys projected capacity is 50,000m3. An international consortium, consisting of Deutsche Gesellschaft zum Bau und Betrieb von Endlagern fuer Abfallstoffe mbH (Germany), Gesellschaft fuer Anlagen— und Reaktorsicherheit mbH (Germany), Posiva Oy (Finland), AEA Technology (United Kingdom), Institutt for energi teknikk (Norway), and Svensk Kaernbraenslehantering AB (Sweden), is assessing the project’s safety. (7) Environmentalists oppose the plan due to safety concerns as well as fears that imported spent nuclear fuel may eventually be stored at the site. Arkhangelsk Governor Anatoliy Yefremov has denied this,. saying that all wastes will originate in northwest Russia. (8)

Another proposal for dealing with the problem of spent fuel, nuclear reactors, and radioactive waste from nuclear powered submarines involves the use of underground nuclear explosions to vitrify the spent fuel and radioactive waste in tunnels at the Central Atomic Test Site on Novaya Zemlya. The proposal, first introduced in 1994, soon met with opposition over the possibility that the explosions might violate the CTBT. Nevertheless, at the request of Boris Yeltsin, the Central Physical—Technical Institute (TsFTI) in Sergiyev Posad developed techniques for implementing the project, which never came to fruition. (9) In June 1999, TsFTI Chief Scientific Associate Leonid Yevterev and several other scientists published an article in Nezavisimoye voyennoye obozreniye, again making an argument for the implementation of their plan. (10) Although there has been no mention of this scheme more recently, if nuclear testing were to resume in Russia, the idea of disposing of nuclear waste by using nuclear explosions is likely to resurface.

Sources

(1) Okhrana okruzhayushchey sredy, Russian Ministry of Natural Resources Web Site, http://www.mnr.gov.ru/index.php?8+2+&glava=37; M. Kondratkova, Novaya Zemlya: Unexpected View on Possibility of Use, Atompressa, No. 13, April 1999, in Use of Novaya Zemlya for Radwaste Storage, FBIS Document FTS19990602001203; Yadernyy mogilnik na Novoy Zemle? Volna, April 14, 1998, p. 7; Na arkhipelage Novaya Zemlya planiruyetsya postroit khranilishche yadernykh otkhodov, Interfax, July 5, 2001.

(2) Na sostoyavshemsya 22 maya zasedanii kollegii Minatoma Rossii obsuzhdalsya vopros o stroitelstve na arkhipelage Novaya Zemlya mogilnika dlya zakhoroneniya radioaktivnykh otkhodov sredney i nizkoy stepeni aktivnosti, Nuclear.ru, www.nuclear.ru, 23 May 2002.

(3) Russian Environmentalists Opposed to Nuclear Waste Burial on Arctic Archipelago, Interfax, 27 May 2002.

(4) Ivan Moseyev, Mogilnyy proyekt dostalsya Arkhangelsku, Delovoy Peterburg, May 22, 2001, p.7; in WPS Yadernyye materialy, No. 22, June 8, 2001.

(5) Nadezhda Breshkovskaya, Komu bolshe nuzhen yadernyy mogilnik na Novoy Zemle: nam ili gosudarstvu? Pravda Severa, February 20, 2001, in WPS Yadernyye materialy, No. 12, March 23, 2001.

(6) Novosti, Russian Nuclear Web Site, http://www.nuclear.ru/news/full/690.shtml, February 8, 2002; Na sostoyavshemsya 22 maya zasedanii kollegii Minatoma Rossii obsuzhdalsya vopros o stroitelstve na arkhipelage Novaya Zemlya mogilnika dlya zakhoroneniya radioaktivnykh otkhodov sredney i nizkoy stepeni aktivnosti, Nuclear.ru, 23 May 2002.

(7) Ivan Moseyev, Mogilnyy proyekt dostalsya Arkhangelsku, Delovoy Peterburg, May 22, 2001, p.7, in WPS Yadernyye materialy, No. 22, June 8, 2001.

(8) Russian Environmentalists Opposed to Nuclear Waste Burial on Arctic Archipelago, Interfax, 27 May 2002.

(9) Viktor Litovkin, Yadernyy vzryv pod grifom sekretno, Izvestiya, May 6, 1997, p. 5.

(10) Leonid Yevterev, Vladimir Klimenko, Varfolomey Korobushin, Vladimir Loborev, Anatoliy Panshin, Klin klinom vyshibayut, Nezavisimoye voyennoye obozreniye, No. 23, June 18—24, 1999, p. 5.

Notes

(1) Thom Shanker, “US Says Russia Is Preparing Nuclear Tests,” The New York Times, www.nytimes.com, May 12, 2002.

(2) Reuters, May 12, 2002.

(3) This is not the first time the Russian government has issued denials in response to press allegations of CTBT violations by Russia at the Novaya Zemlya test site. In May 2001, the Russian Foreign Ministry issued denials of US press reports that Russia had violated CTBT provisions. According to the ministry, the allegations were an attempt to provide cover for US plans to launch a new round of nuclear weapon modernization. “MID RF nazyvayet domyslami utverzhdeniya SMI SShA o narushenii Moskvoy Dogovora o zapreshchenii yadernykh ispytaniy,” Interfax, May 25, 2001. In August 1997 several US newspapers ran articles alleging the US government suspected Russia of carrying out an underground nuclear test at Novaya Zemlya that subsequently turned out to be an earthquake. Lynn R. Sykes, “Small Earthquake Near Russian Test Site Leads to US Charges of Cheating on Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty,” F.A.S. Public Interest Report, http://www.fas.org/faspir/pir1197.htm.

(4) Interfax, May 12, 2002; in “Russia: Ivanov denies Russia preparing to conduct nuclear tests on Novaya Zemlya,” FBIS Document CEP20020512000067.

(5) Dmitriy Panovkin, ITAR-TASS, May 17, 2002; in “Russia: Foreign Ministry denies US claims of Russian resumption of nuclear tests,” FBIS Document CEP20020517000428.

(6) Aleksandr Ovchinnikov, “Western Media Reports on Russia Resuming Nuclear Tests Are Untrue,” RIA Novosti, May 18, 2002.

(7) “Rossiya provela seriyu ‘neyadernovzryvnykh eksperimentov’ na Novoy Zemle – Minatom,” Interfax, November 3, 2000.

(8) Thomas Nilsen and Igor Kudrik, “Russia Performed Three Subcritical Nuclear Tests,” Bellona Foundation, http://www.bellona.no/imaker?id=17814&sub=1, September 8, 2000.

(9) Kirill Belyaninov, “The Administration of the US is ready to Resume Nuclear Explosions,” Novyye izvestiya, January 11, 2002; in “Claim that Defense Ministry’s 12th Main Directorate in Favor of Resuming Tests,” FBIS Document CEP20020111000320.

(10) Vladimir Orlov, “Ugroza yadernogo terrorizma v Rossii sushchestvuyet,” Moskovskiye novosti, June 28, 1995; in Integrum Techno, www.integrum.ru.

(11) Vitaliy Tretyakov, “Yevgeniy Adamov: ‘Russia’s Nuclear Complex is Still Alive, Though It Has Suffered a Few Amputations.’ Minister of Atomic Energy Describes His Sector’s Problems and Prospects,” Nezavisimaya gazeta, March 20, 2001, pp. 1, 8; in “Atomic Energy Minister Adamov Interviewed,” FBIS Document CEP20010321000290.

(12) “Yadernaya energetika i opasnost rasprostraneniya yadernogo oruzhiya. Strany ‘yadernogo kluba’ – garanty stabilizatsii ili vdokhnoviteli novykh yadernykh ispytaniy?,”Agentstvo informatsionnogo vzaimodeystviya, April 11, 2002.

(13) “Nelzya isklyuchit vozmozhnost khishcheniya yadernykh materiyalov,” Yadernyy kontrol, No. 34/1997; in Integrum Techno, http://www.integrum.ru/.

(14) Kirill Belyaninov, “The Administration of the US is ready to Resume Nuclear Explosions,” Novyye izvestiya, January 11, 2002; in “Claim that Defense Ministry’s 12th Main Directorate in Favor of Resuming Tests,” FBIS Document CEP20020111000320.

(15) “Treaty Between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Limitation of Underground Nuclear Weapon Tests (and Protocol Thereto),” US Department of State, http://www.state.gov/www/global/arms/treaties/ttbt1.html.

(16) Keith Rogers, Russian diplomat to tour test site, Las Vegas Review-Journal online edition, http://www.lvrj.com/cgi-bin/printable.cgi?/lvrj_home/2001/Jul-06-Fri-2001/news/16479971.html, July 6, 2001.

(17) The United States has conducted 1,030 nuclear tests more than all other nuclear-armed nations combined. In 1992, the US stopped nuclear testing. This act was instrumental in pushing forward the indefinite extension of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1995 and the global opening for signature of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) in 1996. A contentious issue was whether to make the CTBT a zero-yield treaty, i.e., to ban all nuclear explosions. After much arduous debate and the adverse international reaction to the 1995 series of French nuclear tests, the negotiators agreed to include zero-yield as a key principle. However, the CTBT did not prohibit subcritical tests. These tests often use small amounts of plutonium to investigate the effect of aging on this elements chemical structure. All types of non-nuclear testing are allowed.

(18) According to US standards, safety refers to guaranteeing that nuclear weapons will only explode when so ordered and that during an accident the probability of producing a nuclear yield greater than four pounds of TNT is about one in a million. Reliability means that if a nuclear weapon is exploded, the explosive yield will be within the design parameters. In other words, a reliable weapon would be assured of producing the intended destructive power.

(19) The Los Alamos National Laboratory and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory both conduct subcritical tests at the Nevada Test Site, the complex built for the previous full-scale nuclear tests. The subcritical testing facility is designated U1A. It used to be called the Low Yield Nuclear Experimental Research (LYNER) facility. As the old name implies, this 300 meter deep complex was originally designed to contain low-yield nuclear tests. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Underground Explosions are Music to Their Ears, http://www.llnl.gov/str/Conrad.html.

(20) Frank von Hippel and Suzanne Jones, Take a Hard Look at Subcritical Tests, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, November/December 1996, http://www.bullatomsci.org/issues/1996/nd96/nd96vonhippel.html.

(21) Report on the Defeat of Hardened and Deeply Buried Targets, Sec. 1018, S. 2549, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2001 (The full text can be found at http://thomas.loc.gov).

(22) However, research that could lead to new nuclear weapons development continues. In April, DOE and DOD launched a new feasibility study on earth-penetrating weapons against hardened and deeply buried targets. A major component of this study is to examine the role of new nuclear weapons for this mission. At this stage, there are too many uncertainties to determine whether such a study alone would lead to renewal of nuclear testing. Nevertheless, the pattern of related events as discussed below could be pointing toward renewed testing. Presently, domestic and international political factors pose substantial barriers to testing. Philipp C. Bleek, “Energy Department to Study Modifying Nuclear Weapons,” Arms Control Today 32 (April 2002), http://www.armscontrol.org/act/2002_04/nucapril02.asp.

(23) Daryl G. Kimball, CTBT Rogue State? Arms Control Today, December 2001, http://www.armscontrol.org/act/2001_12/ctbtanalysisdec01.asp.

(24) Philipp C. Bleek, White House to Partially Fund Test Ban Implementing Body, Arms Control Today, September 2001, http://www.armscontrol.org/act/2001_09/ctbtsept01.asp.

(25) The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, Press Briefing by Ari Fleischer, January 9, 2002, http://www.fas.org/nuke/control/ctbt/news/010902a.htm.

(26) J.D. Crouch, ASD ISP, Special Briefing on the Nuclear Posture Review, January 9, 2002, http://www.defenselink.mil/news/Jan2002/t01092002_t0109npr.html.

(27) Prepared Statement of John S. Foster, Jr., Panel to Assess the Reliability, Safety, and Security of the United States Nuclear Stockpile, House Armed Services Committee, March 21, 2002, http://www.house.gov/hasc/openingstatementsandpressreleases/107thcongress/02-03-21foster.html.

(28) National Nuclear Security Administration, FY2003 Budget Request, Executive Summary, http://www.mbe.doe.gov/budget/03budget/content/nnsaadm/nnsaover.pdf; Robert Civiak, The Department of Energy Fiscal Year 2003 Budget Request for Nuclear Weapons Activities, Tri-Valley CAREs, http://www.trivalleycares.org/2003budgetanalysis.asp.

(29) Wade Boese, US Reportedly to Study Nuclear Warheads for Missile Defense, Arms Control Today, May 2002, http://www.armscontrol.org/act/2002_05/nucmisdefmay02.asp.