- Brodie Anderson

- Doctor Thomsen

- Patricia Newman

- Bits of Humor

- Not By Bread Alone

- The Curious Incident

- 2nd Chances

- Walt Atchison

Second Chances

Paul C. White

Los Alamos National Laboratory, Ret.

and

Anastasia Chirkina-Travaglini

Travaglini Design

Download in PDF

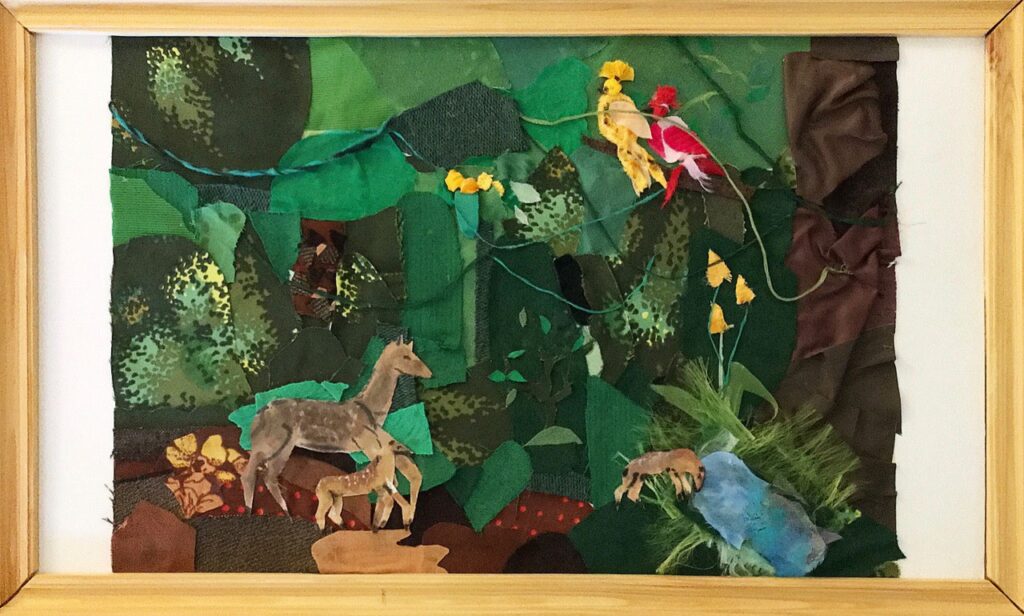

“Paul! There are some girls downstairs looking for the tall guy with white hair and glasses. That must be you.” That was the cry from one of my colleagues on a cool October evening in Snezhinsk, Russia in 1993. We were preparing for the bus ride to the airport the next morning at the end of the first, week-long Surety Technology Symposium at RFNC-VNIITF. But who could resist such a summons. So, I interrupted my packing and made my way to the hotel lobby, where I was greeted by a small group of Russian school girls. Leading the charge was a bright-eyed, somewhat tomboyish girl, who spoke better English than the others, and who presented me with a gift – a framed, fabric and thread collage depicting a nature scene. They had all signed the cardboard backing, but the instigator – and the subject of this story – was Anastasia, or Nastya for short.

Collage made by Snezhinsk students as a gift to Paul White, English Students with the Americans (1993)

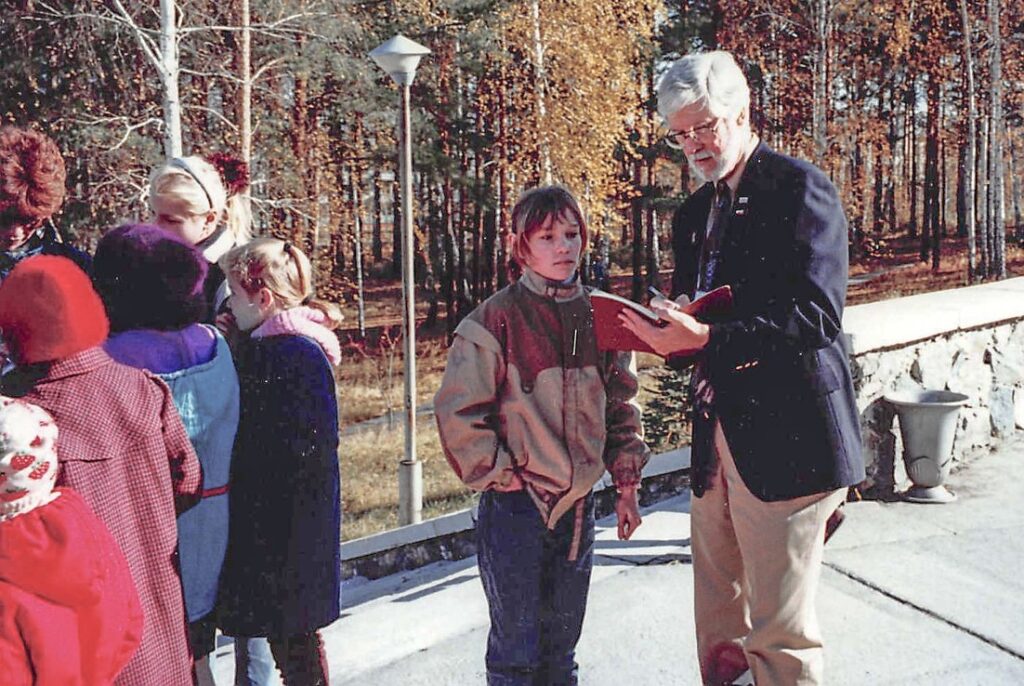

I had first encountered Nastya and the others a few days earlier, during a break between Symposium sessions. Our meetings were held in the Children’s Musical School of Snezhinsk, and one bright afternoon, a couple of us walked down the steps to visit with a group of elementary kids (5th form, or so) who seemed eager to encounter some of these American strangers in town. They must have been on assignment to ask about some English words. But I had been cramming some Russian vocabulary, and tried to make a game of answering with the Russian word when one of them pointed at a picture in their book. Nastya was particularly amused by this game, pressed hard to get me to answer in English, and laughed delightfully when I messed up the Russian. She and the rest of the group were back again the next day for another ‘English’ encounter. What fun – and what an enjoyable added dimension to the more serious business of the symposium. The gift, the collage was a bonus, and the encounter itself proved just a beginning.

Anastasia and Paul, Outside Snezhinsk Music School (1993)

English Students with the Americans (1993)

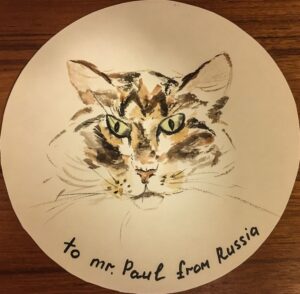

Within ten days of our leaving Snezhinsk, Nastya had written a letter, perhaps with help from her English teacher, but with a beautiful hand all her own, and figured out how to get it to me through a traveling institute scientist. We exchanged letters and small presents using such willing couriers over the next several years. Barbie Doll accessories and craft supplies were among her favorites, and I was blessed with increasingly fine examples of her burgeoning artistic talent.

Cat Watercolor by Anastasia (1995)

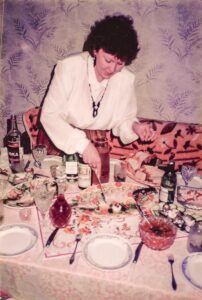

Anastasia’s Mother with Sinara Pike Creation (1995)

A return trip to Snezhinsk a year or so later brought a memorable re-encounter. Throughout our interactions with the closed nuclear cities, visits to private residences were a real rarity. Indeed, they were virtually impossible by the late 1990s. I don’t know what strings were pulled by Nastya’s parents, who both worked at the institute, but I was invited to dinner at their flat on that return visit. The meal was spectacular, centering around exquisitely prepared pike from the nearby Lake Sinara. It took most of the day to fix the fish and all the trimmings that went with it.

Nastya did her best with her limited English to bridge our linguistic differences, but we were helped substantially by the interpreter (probably security) that joined us for the evening. Now, more than twenty years later, I can still remember the taste of that fish, and the warmth of that shared family meal.

Anastasia’s Family in Their Flat (1995)

We exchanged many more letters during the rest of that decade, and there was one more, equally memorable dinner with Nastya’s family during a later visit. But in 1999 Nastya was off to university in St. Petersburg, and willing ‘mailmen’ were much harder to find. Our communication came inevitably to a halt. Ever resourceful, however, Nastya recruited a friend to hand carry a letter (and small gift) on her trip to the US for a temporary work assignment. Imagine my surprise to get a call from that friend, Natasha, inviting me to stop by her home in Santa Fe to pick up a letter from Nastya. This was our first ‘second chance.’ Now I had a St. Petersburg address and email, and exchanges resumed, even if they were intermittent. We caught each other up on family news, her educational successes, changes in my work, and various personal adventures. After finishing her time at university, she worked for a Russian-Italian furniture design company, further expanding her already broad horizons. But with address changes – both postal and electronic – and other distractions, this link eventually proved fragile as well. We lost contact.

Then last year, with work on Doomed to Cooperate wrapping up after its July publication, I joined others of the editorial team in launching an electronic archive to complement the book. Among other possibilities, we wanted to include personal stories and anecdotes to add a human dimension to the story of our Lab-to-Lab interactions. I thought of Nastya and how delightful it had been to know each other and to share a part of our lives totally separate from work or laboratories. Then, like a not-so-subtle knock on the head, Facebook popped to mind. I searched using Anastasia’s full name and found several possible matches, but from the resemblance of one profile picture to my most recent St. Petersburg photos from Nastya, I knew I had found her. She quickly accepted a ‘Friend Request,’ and now we are reconnected. Another ‘second chance.’ Through our regular Skype visits, I know Nastya moved to Italy in 2010. She is now happily married, lives in Milan, runs her own free-lance web design company, and teaches art on weekends. She exhibits the same outgoing, creative, vivacious spirit that made her reach out to the stranger that came to her closed Russian town so many years ago. Now we retrace our respective family stories, fill in gaps, and laugh over recollections of our own story. We also imagine meeting again one day in this country or in Italy.

Anastasia and Her Husband in Italy (2016)

This is just one of many personal narratives that branch out from the Lab-to-Lab interactions between US and Russian nuclear institutes. Nastya and I were never professional colleagues. We became pen-friends and more, and what we have shared transcends national boundaries, cultural divides, and any political differences. Our friendship reminds me that the root of the successes achieved in those Lab-to-Lab exchanges really lies in the personal relationships that formed and grew and continue to this day.